By Shari Narine

Windspeaker Writer

December 3, 2015

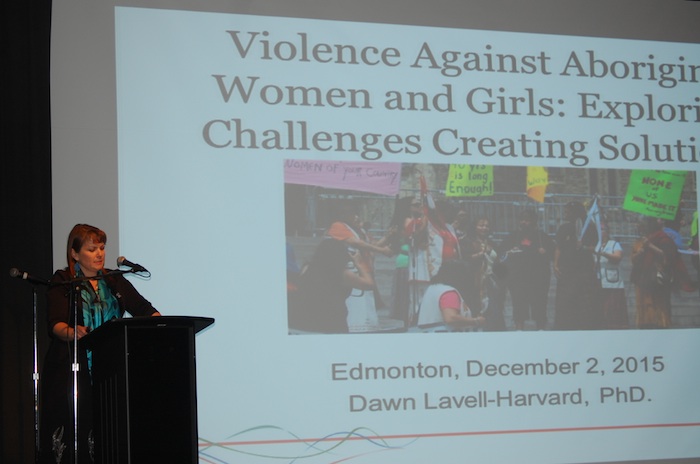

Dawn Lavell-Harvard was moved to tears last night when she relayed her young daughter's concern after hearing her mother do an interview with CBC Radio about violence and rates of homicide for Indigenous women. Asked Lavell-Harvard’s preteen: “We’re Native, right? And I’m a girl, right? Mom, does that mean I’m in danger?”

As an Aboriginal female, based both on statistics and anecdotal evidence, Lavell-Harvard would have to answer yes. And that scares her for her three daughters. And it keeps her on task.

“In a society where women are devalued and Aboriginal people are dehumanized, Indigenous women are the lowest of the low on a scale of who matters and who doesn’t,” said Lavell-Harvard.

And nothing will change until the make-up of the people who care about what is happening to Aboriginal women and girls changes.

Take the audience who filled the theatre at the Stanley Milner library in downtown Edmonton to hear Lavell-Harvard, president of the Native Women’s Association of Canada, talk about the challenges facing Aboriginal women. They were mainly women, mainly Aboriginal women, with a smattering of men, both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal

“As long as it’s seen as an Aboriginal issue, specifically an Aboriginal women’s issue, we are always going to be focusing on treating the symptoms. Crisis intervention. Mopping up after the fact,” said Lavell Harvard.

While the majority of men are not violent against women, the majority of violence against women is caused by men. And, Lavell-Harvard holds, men know about the violence and remain silent. That silence is complicity. Men need to become part of the conversation.

"If I got every Aboriginal woman, along with her kids and their hubbies, and their grandpas and their brothers and their uncles and put them on Greyhound buses and drove them all to Ottawa, it would still be such a small whisper that the government writes it off that this is not an issue for the general Canadian population. So having those allies come and hear what’s going on, that’s what’s going to make a difference,” she said.

Lavell-Harvard presented startling statistics, but none of them new: the RCMP says close to 1,200 Indigenous women have been murdered or gone missing since the mid-1980s; the majority of women who fall into the 1,200 number are between the ages of 19-30; Aboriginal women are eight times more likely to be killed than non-Aboriginal women; and over 40 per cent of Aboriginal women live in poverty. But it’s not all statistics, she says, referring to the more recent occurrence in Val d’Or, where members of the police department have been accused by a dozen Aboriginal women of mistreatment and being solicited for sexual favours.

It’s not that the women are vulnerable, says Lavell Harvard, it’s that they are in vulnerable situations.

Lavell-Harvard called on people in attendance to speak out, whether ate their workplaces, their corporations, their unions, their churches, their families.

“We can’t let this be an Aboriginal issue. We have to join together and start to make a difference. We have to do something,” she said.

While she lauded Prime Minister Justin Trudeau for his commitment to hold a national inquiry into murdered and missing Indigenous women, Lavell-Harvard said it was important that recommendations that come from the inquiry are followed up with legislation and a realistic budget.

“We have to keep the pressure on. Hold their feet to the fire. Hold them accountable… to have a solid national action plan. The inquiry is just the first step to identify the problems,” she said.